Unlike in the U.S., there are no provisions for the filing of continuation or continuation-in-part (CIP) applications in Canada. However, rights seekers can still pursue and maximize protection by understanding and taking advantage of some of the differences between U.S. and Canadian patent practice.

Divisional applications and double patenting

The Canadian Patent Act allows for the filing of divisional applications. Divisional applications are primarily used in Canada to prosecute claims that have been cancelled from a parent application due to a unity of invention objection. Nonetheless, it is possible in Canada to treat a divisional application like a continuation application, but caution must be exercised to avoid double patenting problems.

Specifically, if claims are pursued in a divisional application in Canada that were not cancelled from the parent application due to a unity of invention objection, then double patenting problems can arise if the claims of the divisional application are not patentably distinct from the claims of the parent. Unlike U.S. practice, such an objection cannot be addressed in Canada by the filing of a terminal disclaimer.

However, a patent applicant can add all claims of interest to the Canadian parent application and then file a divisional application if/when the Canadian Examiner raises a unity of invention objection.

As the Canadian Patent Office does not have excess claim fees, all claims of interest can be added to the Canadian parent application without attracting additional government fees. If a unity objection is raised and claims are cancelled in response to such an objection, then the cancelled claims will be immune from double patenting when pursued in a divisional.

The one-year grace period

Like the U.S., Canada also has a one-year grace period, which means that if the invention has been publically disclosed by the inventors or the applicant, it may still be possible to pursue patent protection in Canada.

However, unlike in the U.S., the one-year grace period in Canada is calculated from the filing date in Canada, not the priority date. In the case of a Canadian national phase of a PCT application, the filing date in Canada is deemed to be the PCT international filing date.

For CIP applications filed in the U.S., a corresponding patent application can be filed in Canada. Given the grace period, docketing to file in Canada should be within one year of the publication date of the U.S. parent application to avoid the U.S. parent application being citable against the Canadian application for the purposes of novelty and obviousness.

Filing a patent application in Canada when there is a CIP in the U.S.

A few considerations must be kept in mind when filing a patent application in Canada and when there is a CIP in the U.S. These are discussed in more detail below in the context of some hypothetical scenarios.

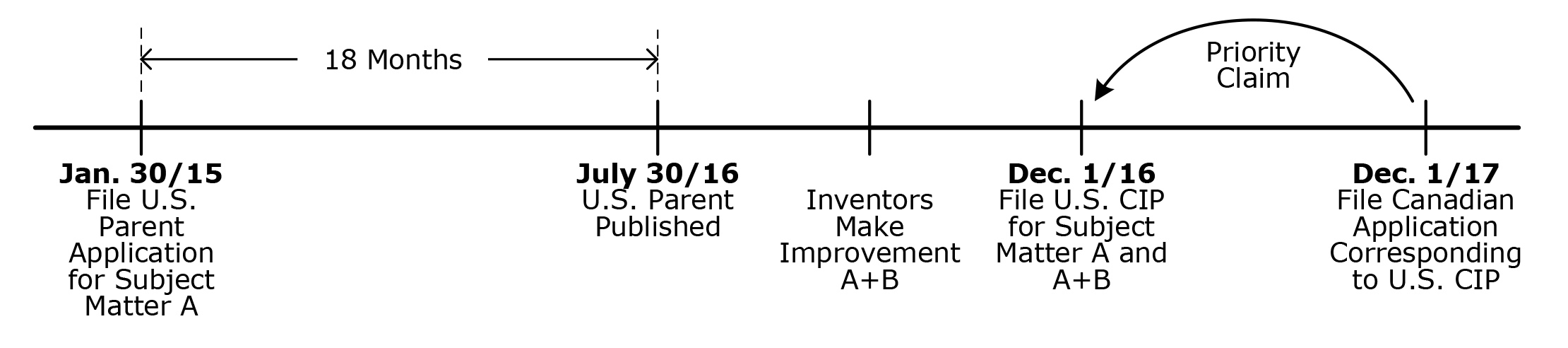

Hypothetical scenario #1:

Improvement A+B is made by the inventors, and it is desired to pursue patent protection in Canada for the improvement.

A patent application may be filed in Canada within one year of the filing date of the U.S. CIP, and claim priority back to the filing date of the U.S. CIP, as illustrated. However, the priority claim in Canada is only valid in respect of the new subject matter A+B added in the U.S. CIP.

Also, the publication of the U.S. parent application on July 30, 2016 is citable against the Canadian patent application for the purposes of novelty and obviousness. This can be avoided by instead filing the Canadian application within one year of the publication date of the U.S. parent, i.e. before July 30, 2017.

Recommended strategy:

Pursue claims in Canada that correspond to the new subject matter added in the CIP filing. Docket to file in Canada within one year of the publication date of the U.S. parent.

If the Canadian application is filed more than one year after the publication date of the U.S. parent, then ensure that all of the Canadian claims are novel and non-obvious over the disclosure in the U.S. parent.

If there are claims in the Canadian application that are directed to the original subject matter in the U.S. parent application, then assume that no priority claim can be validly made for such claims. Moreover, the Canadian application will need to be filed within one year of the publication date of the U.S. parent to avoid the U.S. parent publication anticipating such claims.

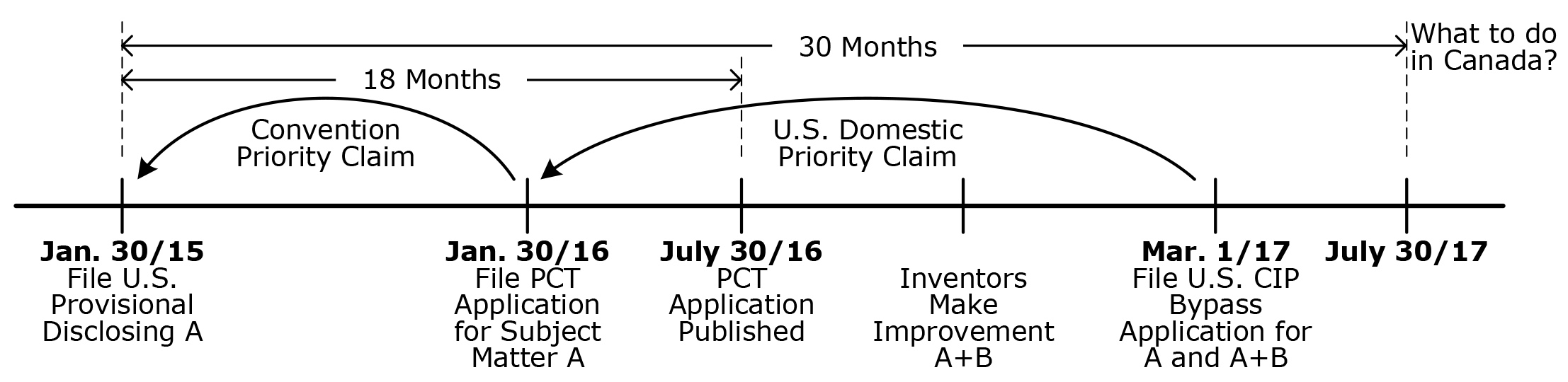

Hypothetical scenario #2:

Many Canadian applications are a national phase entry of a PCT application. Consider the scenario below:

Filing a U.S. CIP as a bypass application, rather than entering national phase in the U.S., is a filing strategy that may work well in the U.S. to pursue claims directed to A and A+B in a single U.S. application. What should be done in Canada?

One option for the Canadian prosecution is to enter national phase off of the PCT application, which can be done as late as 42 months after the priority date if a late fee is paid. The potential downside to keep in mind is that the Canadian national phase entry would not include the new subject matter A+B added in the U.S. CIP application.

Additionally, or alternatively, a Canadian regular application may be filed within 12 months of the filing date of the U.S. CIP application and make a priority claim back to the U.S. CIP application. The following should be kept in mind. The Canadian priority claim would only be valid in respect of the new subject matter A+B in the CIP. Also, the Canadian regular application should be filed within 12 months of the publication date of the PCT application, or otherwise the PCT publication would be citable against the Canadian regular application for the purposes of novelty and obviousness.

Recommended Strategy:

Enter national phase in Canada to pursue the subject matter A in the original PCT application. Also file a regular Canadian application claiming priority back to the filing date of the U.S. CIP application in order to just pursue the new subject matter A+B added in the U.S. CIP application. File the regular Canadian application within 12 months of the publication date of the PCT application to avoid the PCT publication being citable for novelty and obviousness against the regular Canadian application. Coordinate the Canadian prosecution to ensure that there are no obviousness-type double patenting problems between the Canadian national phase entry and the Canadian regular application.

Conclusion

It may not always be possible to copy a U.S. filing strategy in Canada, particularly when a continuation or CIP application has been filed in the U.S. However, understanding the differences above will help rights seekers to understand and maximize patent protection in Canada.

To find out more speak to a member of our firm’s Patent group.

The preceding is intended as a timely update on Canadian intellectual property and technology law. The content is informational only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. To obtain such advice, please communicate with our offices directly.

Related Publications & Articles

-

Federal Court confirms test for leave to file new evidence in appeal from Opposition Board Decision

As of April 1, 2025, subsection 56(5) of the Trademarks Act requires parties to obtain leave to file additional evidence on appeal from decisions of the Registrar of Trademarks (the “Registrar”), whic...Read More -

Top five 2025 trends in Canadian copyright law

2025 saw incremental developments in Canadian copyright matters anticipated to set the foundation for potentially major changes in the coming years in AI and accessible remedies for infringement and h...Read More -

Patenting AI: Shift the focus to do it better

Patent protection is pursued for all types of technologies. Why should anything be different just because the technology is based on artificial intelligence (AI)? Nothing is different when reduced to...Read More