The Federal Court recently had occasion to revisit the issue of confusion between foreign-language trademarks involving the use of Chinese characters in Canada.

The litigants in this matter are no strangers to each other. In the early 2010s, the Applicant Cheung’s Bakery Products Ltd (CBP) successfully prevented the registration of trademarks which were applied for by an entity related to the Respondent

Easywin Ltd (Easywin).

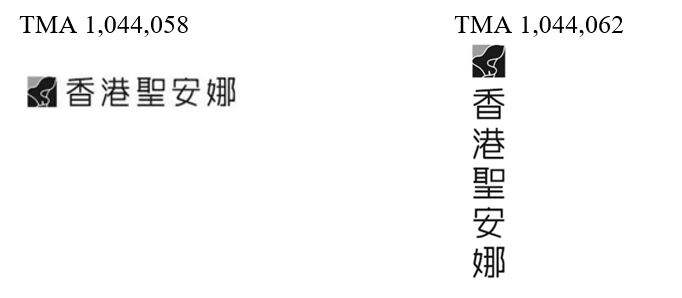

In the present case, CBP succeeded, as it had in the past, on the basis of its Chinese character trademarks. The Court granted its application to expunge from the Trademark Register the following two Chinese Character and Design marks, both registered in the name of Easywin (2023 FC 190):

(collectively, the “Easywin Marks”)

The Court declared that the Easywin Marks were invalid on the bases that (i) they are confusingly similar to the trademarks asserted by CBP and (ii) they were filed in bad faith.

Smart & Biggar successfully represented CBP led by Evan Nuttall and Kwan Loh, alongside Matthew Burt and Matthew Norton.

Background

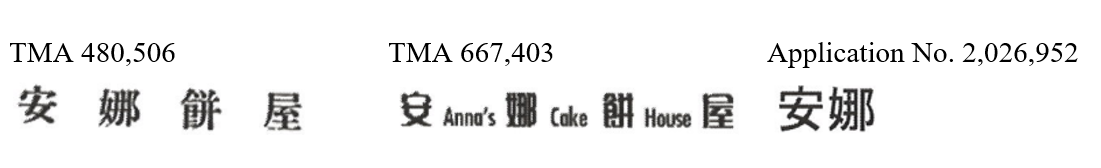

For nearly 50 years, CBP has operated “Anna’s Cake House”, an award-winning, family-owned bakery business in the Greater Vancouver Area offering bakery-related products and services in association with one or more of the following trademarks featuring Chinese characters:

(collectively the “Cheung Marks”)

The Respondent Easywin is a part of the Saint Honore Group of companies, which operate one of the largest chains of bakery stores in Hong Kong and also make and sell bakery-related food products for distribution in Hong Kong, China and foreign markets,

including in Canada.

In July 2019, unbeknownst to CBP, Easywin obtained registrations for the Easywin Marks, both of which comprise the identical two Chinese characters 安娜 that are found in each of the Cheung Marks translating into English as “Anna” or “Anna’s”

and transliterating to “an na” (in Mandarin) or “on naa” (in Cantonese).

Subsequently, in February 2021, CBP brought an application against Easywin in the Federal Court seeking to expunge the Easywin Marks on the grounds of trademark confusion and bad faith.

Trademark Confusion

The Court confirmed that whether a mark is likely to cause confusion is a question that is to be asked in respect of the particular market in which the goods or services are offered.

As was the case in CBP’s previous successes, the Court inferred from the evidence in this case that the likely consumers of the parties’ goods and services would be able to read and understand Chinese characters. The Court noted, for example,

that both parties primarily target their goods and services to the Chinese Canadian community and that they use Chinese characters consistently in their marketing materials, suggesting

that they both believe many of their customers will be able to read and understand them.

Therefore, the Court held that rather than interpreting the parties’ Chinese character marks simply as design elements, as suggested by one of Easywin’s experts, the relevant consumer would understand their meaning and construe them in this

light.

Given that each of the parties’ marks shared the same two Chinese characters 安娜 (meaning “Anna” or “Anna’s”) as dominant elements, the Court found that the parties’ trademarks were similar in appearance, sound,

and in the ideas suggested. While the similarities in appearance were somewhat diminished by the balance of the parties’ marks, this was not sufficient to disturb the Court’s finding that the marks resembled one another.

The other factors which are to be considered in the confusion analysis, including the length of time that the marks were in use, and the extent to which the parties’ goods and services overlap, also favoured CBP. The Court concluded that the relevant

consumer would be likely to think that Easywin was the same source of the bakery products as CBP.

Bad Faith

The Court also held that the Easywin Marks were invalid because the applications from which they were registered were filed in bad faith.

At the time of filing their trademark applications, Easywin was familiar with CBP and knew that they targeted the same consumers and sold the same types of bakery-related goods and services in association with the Cheung Marks. Easywin was also aware

of the above-noted previous dispute between its sister company and CBP.

Notwithstanding the above, Easywin filed for and obtained the registrations only two years after the dispute between CBP and Saint Honore had been resolved in CBP’s favour.

Overall, the Court concluded that Easywin ignored facts that should have given it pause before filing the trademark applications and could not have been satisfied that it was entitled to register the Easywin Marks.

Conclusion

The Court’s decision highlights the importance of identifying the relevant consumer, particularly in circumstances involving foreign character marks. The ability of the relevant consumer to read and understand the foreign characters can significantly

impact how the marks are interpreted for the purposes of assessing confusion.

See our previous article that explores strategies to help brand owners keep control of their key trademarks in all languages (“Strong trademark jumps the language barrier; foreign-language mark refused in Canada”).

If you have any questions on trademark protection or for more information on this topic, please contact a member of our Trademarks & Brand Protection team.

The preceding is intended as a timely update on Canadian intellectual property and technology law. The content is informational only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. To obtain such advice, please communicate with our offices directly.

Related Publications & Articles

-

Federal Court confirms test for leave to file new evidence in appeal from Opposition Board Decision

As of April 1, 2025, subsection 56(5) of the Trademarks Act requires parties to obtain leave to file additional evidence on appeal from decisions of the Registrar of Trademarks (the “Registrar”), whic...Read More -

Top five 2025 trends in Canadian copyright law

2025 saw incremental developments in Canadian copyright matters anticipated to set the foundation for potentially major changes in the coming years in AI and accessible remedies for infringement and h...Read More -

Patenting AI: Shift the focus to do it better

Patent protection is pursued for all types of technologies. Why should anything be different just because the technology is based on artificial intelligence (AI)? Nothing is different when reduced to...Read More