Summary

Last week, the Federal Court of Canada issued its long-awaited decision in Energizer Brands, LLC v Gillette Company, 2023 FC 804.

The case is noteworthy because it is a “comparative advertising” case, and one of only a few that have dissected section 22 of the Trademarks Act.

Section 22 prohibits “depreciation of goodwill” and, similar to the U.S. cause of action for trademark “dilution”, it protects against the “use a trademark registered by another person in a manner that is likely to have the

effect of depreciating the value of the goodwill attaching thereto”.

The Court decided that Duracell’s use of Energizer’s registered trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX in its comparative advertising campaign contravened section 22, and awarded Energizer a permanent injunction, restraining Duracell from

using its trademarks, and damages in the amount of $179,000 CAD. The Court dismissed the remainder of Energizer’s action.

The parties have until September 6, 2023 to appeal the decision. At time of writing, neither party has filed a notice of appeal with the Court.

The Court’s decision in Energizer Brands offers some guidance to brand owners who choose to “bandy about” others’ marks, or use implicit references to other brand owners in their comparative advertising, and has seemingly

narrowed the test for depreciation of goodwill set down by the Supreme Court nearly 20 years ago in Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin v Boutiques Cliquot Ltée, 2006 SCC 23.

Notably, the decision seems to stand for the unprecedented proposition that, in assessing depreciation of goodwill, special attention should be paid to the context in which the defendant uses the mark, as well as the placement and size of the mark relative to other, surrounding indicia. Read our full analysis below for more insight.

The Facts

The parties, Energizer and Gillette (which owns the DURACELL battery brand), represent the leading battery brands in Canada and are each other’s biggest competitors. Duracell has the largest market share, while Energizer has the next largest market share.

Between August 2014 and August 2017, and even as recently as January 2020, Duracell sold AA-sized and hearing aid batteries in Canada in packages bearing stickers with performance claims, comparing the longevity of Duracell’s batteries to those of Energizer, by displaying the trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX, as well as the phrases “the bunny brand” and “the next leading competitive brand”:

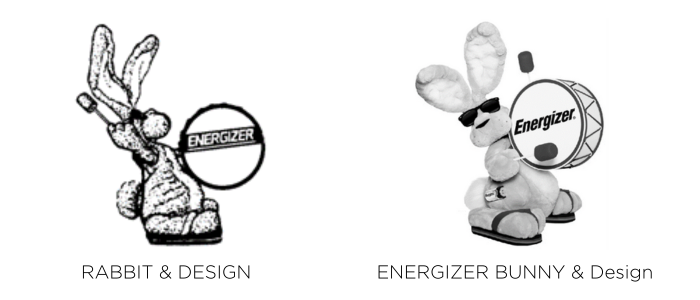

In addition to its well-known trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX, Energizer also owns the registered trademarks RABBIT & Design and ENERGIZER BUNNY & Design (shown below), all for use in association with batteries.

Energizer claimed that Duracell’s packages used its registered trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX in a manner that was likely to have the effect of depreciating the value of the goodwill attached to the trademarks, contrary to subsection 22(1)

of the Trademarks Act.

It also claimed that Duracell’s use of the phrases “the bunny brand” and “the next leading competitive brand” to refer to Energizer depreciated the value of the goodwill attached to its registered trademarks.

The Issue

One of the issues before the Court was whether Duracell used one or more of Energizer’s registered trademarks in a manner likely to have the effect of depreciating the value of the goodwill attaching to the trademark(s), contrary to subsection 22(1)

of the Act.

Depreciation of Goodwill

In assessing whether Duracell had breached subsection 22(1) of the Act, the Court considered the four-part test set down many years earlier by the Supreme Court of Canada in Veuve Clicquot Ponsardin v Boutiques Cliquot Ltée,

2006 SCC 23, in which the famous Champagne house behind VEUVE CLICQUOT Champagne attempted, unsuccessfully, to

enjoin the use of the trademark CLIQUOT by a small group of women’s wear shops in Quebec and Ontario.

The conjunctive test is comprised of four parts, all of which must be established on a balance of probabilities:

- First, a claimant must establish that the defendant used its registered trademark in connection with goods or services. The defendant need not use the mark “as a trademark” (i.e. as a source identifier).

- Second, the claimant must establish that its registered trademark is sufficiently well known to have significant goodwill attached to it. In contrast to the analogous European and U.S. laws, section 22 does not require the mark to be well known or famous, but a defendant cannot depreciate the value of goodwill that does not exist.

- Third, the claimant must establish that its mark was used in a manner likely to have an effect on that goodwill (i.e. linkage).

- Fourth, the claimant must establish that the likely effect would be to depreciate the value of its goodwill (i.e. damage).

With respect to those stickers bearing Energizer’s own trademarks, the Court ruled in favour of Energizer.

In particular, the Court found that: (i) Duracell had indeed used Energizer’s own trademarks “although not for the purpose of distinguishing [its] own batteries”; (ii) substantial goodwill attached to Energizer’s ENERGIZER and

ENERGIZER MAX trademarks, noting that “the trademark ENERGIZER is a well known, if not famous trademark”; (iii) there was the requisite “linkage”, as “the trademarks ENERGIZER and DURACELL are very prominent and hard

to miss, … both on the packages themselves and on any separate in-store displays”; and (iv) there was the requisite “damage”, the complained-of stickers being “examples of an owner’s trademarks being bandied about

resulting in lost control for the owner and lesser distinctiveness”.

With respect to those stickers referring to “the bunny brand”, the Court rejected Energizer’s claim, finding that it had failed to establish the requisite “linkage” between Duracell’s use of the phrase

and Energizer’s trademarks.

The Court found that “the description ‘the bunny brand’ is capable of evoking an image of a bunny that functions as a brand or mark, that is Energizer’s iconic ‘spokes-character,’ the ENERGIZER bunny”, and

understood that “Duracell used the phrase 'the bunny brand' as a shorthand reference to Energizer’s famous ENERGIZER bunny trademark”. It apparently decided that Duracell’s use of the phrase to refer to Energizer’s

famous trademark satisfied the first and second parts of the test, holding that “[b]ecause the reference was not comprised of the registered trademark itself, the only issue in terms of linkage is whether ‘the bunny brand’

was ‘something closely akin to it’” (emphasis added).

But the Court disagreed with Energizer that Duracell’s use of the phrase “the bunny brand” sufficed to establish the requisite “linkage”, finding that “on a balance of probabilities that the average hurried consumer is unlikely to pause long enough at the in-store battery rack to read the [sticker] and to note the reference to ‘The bunny brand’ written in much smaller print”.

Without “any evidence of consumer reaction to the [sticker]”, the Court was “unable to find that Duracell likely depreciated the goodwill in the registered trademark ENERGIZER BUNNY & Design”. While the Court’s decision

does not bar future litigants from successfully claiming depreciation of goodwill where a defendant does not explicitly use its mark, it does suggest that the claimant must adduce evidence to support the requisite “linkage”. Such linkage

will not be assumed, or inferred. In this case, the evidence before the Court simply did not establish the requisite “linkage” between Duracell’s use of the phrase and Energizer’s trademarks.

With respect to those stickers referring to “the next leading competitive brand”, the Court was not persuaded that there was any likelihood of depreciation of goodwill by reason of Duracell’s use of the phrase. In dismissing

Energizer’s claim, the Court made a few interesting observations:

- First, the Court noted that there was no evidence from which it could deduce or infer that the average hurried consumer was going to notice the phrase in the first place. Notably, this factor is not found in the test set down by the Supreme Court, which does not require the hypothetical consumer to first notice or observe the mark or phrase that is the subject of the complaint.

- Second, the Court addressed the matter of “linkage” by asking “whether the consumer would link ‘the next leading competitive brand’ to [a trademark owned by Energizer], not whether the consumer knows who ‘the next leading competitive brand’ is and is familiar with its trademarks”. However, the Court did not find that “the next leading competitive brand” was Energizer, which owns registered rights in its own name (i.e. ENERGIZER, the subject of two trademark registrations upon which Energizer relied).

- Third, the Court found that the “casual observer would not recognize the phrase used by Duracell as a mark of Energizer, and thus, without a ‘link, connection or mental association in the consumer’s mind’ with [a trademark owned by Energizer], there can be no depreciation”. In so finding, the Court did not consider whether the phrase, much like the phrase “the bunny brand”, may be a “shorthand reference” to Energizer and its famous house mark.

Analysis & Takeaways

As the Supreme Court noted in Veuve Clicquot, in 2006, “[s]ection 22 of our [Trademarks] Act has received surprisingly little judicial attention in the more than half century since its enactment”. Consequently, the

Federal Court’s decision in Energizer Brands is of particular importance to brand owners given the Court’s discussion of this cause of action.

Indeed, In Energizer Brands, the Court appears to have made some new observations, which seemingly narrow the test set down by the Supreme Court nearly 20 years ago.

- First, the Court appears to have put significant emphasis on the context in which the complained-of stickers appeared, as the Court held that it should “consider how the parties’ batteries would appear to an average consumer somewhat in a hurry, coming across the batteries in a retail or store setting” in assessing depreciation of goodwill. Notably, the Supreme Court in Veuve Clicquot discussed the hypothetical “somewhat-hurried consumer”, but only in the context of its confusion analysis. In dismissing Energizer’s claim with respect to Duracell’s use of the phrase “the bunny brand”, the Court found that “the average hurried consumer is unlikely to pause long enough at the in-store battery rack … to note the reference to ‘the bunny brand’”.

- Second, and consistent with its emphasis on the context in which the complained-of stickers appeared to consumers, the Court made much of the placement and size of the marks and phrases that are the subject of Energizer’s section 22 claims. In particular, in dismissing Energizer’s claim with respect to Duracell’s use of the phrase “the bunny brand”, the Court noted that “the reference to ‘the bunny brand’ [was] written in much smaller print” (even though the prominent comparison claim was likely meaningless without referring to a specific comparator). Similarly, the Court noted that there was no evidence from which it could be deduced or inferred that the “average hurried consumer” was going to even notice the phrase “the next leading competitive brand” on Duracell’s “busy label”.

- Third, the Court appears to broaden the prohibitive scope of section 22, at least in the context of comparative advertising cases. Paraphrasing Justice Thurlow in one of Canada’s leading comparative advertising cases, Clairol International Corp. et al v Thomas Supply and Equipment Co. et al, 1968 CanLII 1280, the Court noted that the section is intended to prohibit a competitor’s mere use of a registered owner’s trademark “for the purpose of appealing to the owner’s customers in an effort to weaken their habit of buying what they have bought before”. Damage, then, may theoretically be established by evidence of consumers simply changing their buying habits as a result of a comparative advertising campaign.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the Court concluded that Duracell’s use of Energizer’s registered trademarks ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX in its comparative advertising campaign contravened section 22. It awarded Energizer a permanent injunction restraining Duracell

from using its trademarks, and the complained-of stickers bearing its trademarks, on battery packages. In addition, it awarded Energizer damages in the amount of $179,000 CAD for Duracell’s having “bandied about” the registered trademarks

ENERGIZER and ENERGIZER MAX, to the likely detriment of the goodwill attaching to them.

The Court dismissed the remainder of Energizer’s action.

The parties have until September 6, 2023 to appeal the decision. At the time of writing, neither party has filed a notice of appeal with the Court.

If you have any questions about the above, please do not hesitate to contact a member of our firm’s Trademarks or Marketing and Advertising Groups.

The preceding is intended as a timely update on Canadian intellectual property and technology law. The content is informational only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. To obtain such advice, please communicate with our offices directly.

Related Publications & Articles

-

Canadian IP litigation 2025: a year in review

In 2025, Canadian courts addressed a range of issues in intellectual property litigation. Highlights included the imposition of jail time on contumacious copyright pirates, appellate guidance on paten...Read More -

Canadian trademark law 2025: a year in review

2025 marked a year of adaptive reform in Canadian trademark law. Decisions, legislative updates, CIPO initiatives, and procedural enhancements collectively show the system continuing to mature in the ...Read More -

Federal Court confirms test for leave to file new evidence in appeal from Opposition Board Decision

As of April 1, 2025, subsection 56(5) of the Trademarks Act requires parties to obtain leave to file additional evidence on appeal from decisions of the Registrar of Trademarks (the “Registrar”), whic...Read More