As reported in the September/October 2011 issue of IP Connections, a number of recent multi-billion dollar patent portfolio acquisitions demonstrate that valuation of patents may be at an all-time high. Yet some applicants in software-related fields do not take advantage of all the potential patent rights in their innovations. Many applicants understandably have an instinctive tendency to try to protect classical engineering developments – complex, behind-the-scenes algorithms and functioning of their software. However, it is also possible to protect the way software functions from a user's perspective.

What can be protected? In Canada, the Patent Act broadly defines "invention" as "any new and useful art, process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement in any art, process, machine, manufacture or composition of matter." Historically, several of these categories of patent-eligible subject-matter have encompassed computer-related inventions, which can be patented using "art" or "process" claims directed to the functions carried out by the computer, "machine" claims directed to a computer that is programmed to carry out those functions, and "manufacture" claims directed to the software stored on a medium. Although the Canadian Intellectual Property Office ("CIPO") adopted new policies in 2009, which included a number of new restrictions on the patentability of computer-related inventions, recent court decisions have provided clarity and have generally removed these restrictions. In most cases, it is possible to draft claims for software-related inventions that fall within the categories of patent-eligible subject-matter.

It is clear that there is room to claim an invention from the user's perspective, such as by focussing on new and inventive user interface ("UI") elements, ways in which software exchanges information with users, and ways in which software facilitates business activities.

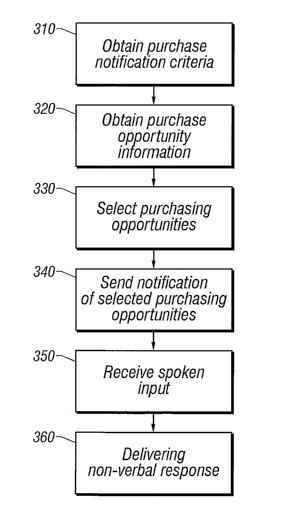

For example, Canadian Patent No. 2,432,194, titled, "Mixed-Mode Interaction," describes a method of facilitating shopping activities by exchange of spoken and non-verbal messages with a wireless communication device. According to one of its claims, a spoken input including purchase notification criteria is received, match information is selected based on the criteria, a non-verbal response based on the match information is returned to the wireless communication device, and a second spoken input is received from the device to authorize a purchase.

FIG. 3 of Canadian Patent No. 2,432,194 (Mamdani et al.)

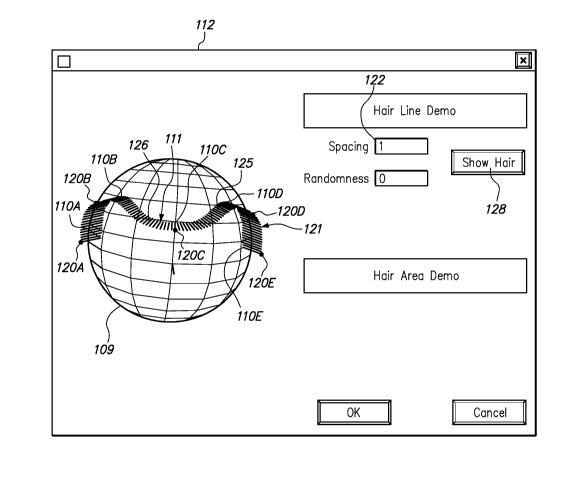

Canadian Patent No. 2,663,693, titled, "Follicular Unit Transportation Planner and Methods of its Use," describes a system for creating a plan for cosmetic hair transplants. The application includes description algorithms for facial modelling and placement of implants. The claimed system calls for a user interface configured to display a three-dimensional model of the body surface, to generate and display a boundary curve with implant locations and orientations based on control points, wherein the user interface allows a user to adjust a location and/or orientation of at least one of the control points.

FIG. 13 of Canadian Patent No. 2,663,693 (Bodduluri)

Why focus on the user's perspective? Claiming an invention from a user's perspective may avoid issues sometimes encountered with software-focussed applications. There may not always be a way to patent the underlying algorithms in a piece of software, but if the algorithms allow the software to interact or exchange information with users in a new way, that new interface may be patentable.

Another benefit is that it may be relatively easy to detect infringers of user-focussed claims. A user interface can simply be observed. Often, the underlying mechanics of an application or device cannot, at least without significant effort.

Even apart from the above considerations, another reason to consider patentability of UI elements is simply to take advantage of all available protection. Whether through licensing, enforcement or other exploitation, every patent right can serve to fortify a market position.

The recent spate of smartphone and tablet computer-related patent lawsuits that have taken place around the world provides prime examples. A great deal of attention has been paid to the exchange of lawsuits between companies like Apple, Samsung, Motorola and HTC in courts and tribunals all over the world. In the context of a class of products that has, in half a decade, revolutionized the computer and cellphone industries and seen handheld devices rival the utility of home computers, one might expect the patent battleground to revolve around miniaturization of processors, telecom infrastructure, battery technology and other classically "high tech" subject matter. However, among the patents Apple has asserted in U.S. courts are U.S. Patent No. 7,657,849, titled "Unlocking a Device by Performing Gestures on an Unlock Image" and U.S. Patent No. 7,469,381, titled "Portable List Scrolling and Document Translation, Scaling and Rotation on a Touch-Screen Display," both of which relate to UI elements. The former, which is among a group that has been referred to by some commentators as "slide to unlock" patents, claims, in part, detecting contact on a touch-sensitive display, moving an unlock image along a predefined displayed path in accordance with the contact and transitioning a device into an unlock state if the detected contact corresponds to a predefined gesture. The latter claims a method of scrolling electronic documents back and forth on a touch screen display in response to detection of movement of a physical object (finger) on or near the display.

The mere fact that these patent families are involved in such extensive and high-profile litigation demonstrates their value. Though the claimed UI elements represent a relatively small part of the product in which they are embodied, if Apple ultimately succeeds in obtaining and enforcing judgments it will undoubtedly gain valuable leverage in a fiercely competitive market.

A lesson to be learned is to consider all possibilities for patent protection: a project's most difficult or most traditional engineering problem may not be the only source of patent rights. New user interface elements, new ways of exchanging information

or facilitating business activities with users, and other user-focussed improvements may present options for increasing the breadth of patent protection. Given the importance patent rights can have to a company's market position, it can pay to be

attuned to all possibilities.

The preceding is intended as a timely update on Canadian intellectual property and technology law. The content is informational only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. To obtain such advice, please communicate with our offices directly.

Related Publications & Articles

-

Ghost in the machine: AI and patent protection

While there are arguments available that the current legal framework in Canada precludes the possibility of patenting AI-generated inventions (i.e., without any human input), it remains to be seen how...Read More -

All clear? The importance of trademark clearance searching in Canada

This article outlines the benefits of trademark searching, different types of searches, and specific Canadian considerations, emphasizing the importance of proactive trademark clearance.Read More -

Angelcare and Playtex seal another win against patent infringer Munchkin

On August 17, 2023, the Federal Court issued its decision in Angelcare Canada Inc. et al. v Munchkin Inc. et al. (2023 FC 1111) regarding the Plaintiffs’ entitlement to certain remedies for patent inf...Read More